Voters in Iraq will go to the poll stations for the second time on 15th December 2005 to elect a new parliament after endorsing Iraq’s new constitution in a referendum on 15th October. Many observers and “anti-war activists” in the West still express scepticism about the emerging system in Iraq. They still question the reasons to remove Saddam Hussein and his regime and the intention behind the US presence in Iraq. The basic question is, though, what the internal political process in Iraq is about.

Re-building the state

The expression often used by American politicians and officials before the war to remove Saddam Hussein and his regime was “regime change”. Soon after politicians, academics and think tank organisations started to see the US task in Iraq to be about “nation-building”. Recently, the US is seen to be involved in democracy-building. However, I believe that the political process in Iraq is much more profound than “regime change”, without having so much to do with nation-building. “Nation-building” is a synonym for “state-building” in American terminology. A more appropriate and realistic view would be see the process as state re-building to accommodate Iraq’s diverse population and to bring about democracy and security in the longer run. Democratic processes, institutions, norms and values would facilitate these goals in a long perspective. Politicians, diplomats, bureaucrats and the military are currently engaged in re-creating, re-structuring and re-shaping the basic elements of the emerging new state.

When Saddam Hussein’s regime melted away under US military confrontation, Iraq’s government and state institutions outside Kurdistan collapsed entirely. Liberation of Iraq from Saddam and his regime turned quickly to a UN-recognised occupation under a US-led coalition. During the first year of changes in Iraq, CPA (Coalition Provisional Authority) and the US-appointed Governing Council (GC) struggled to re-establish some basic institutions and mechanisms to provide security for the US-led coalition forces and the ruling coalition of former exile groups of Shi‘a and Sunni opposition as well as political forces from Kurdistan. Handing over “sovereignty” to political parties, groups and individuals in Iraq was meant to accelerate the political process in Iraq. Several attempts were made to create new police and internal security forces as well as military units. In addition to that coalition forces and officials, together with officials from Iraq, have re-created health, education and other service-oriented institutions, mainly outside of Kurdistan region. By creating an interim government and passing of a temporary constitution in March 2004 (officially known as TAL, Transitional Administrative Law) the political process changed some of its basic mechanisms: Iraq’s political forces were in charge of the political process, at least theoretically. However, with the election of the country’s first post-Saddam Hussein Assembly on 30th January 2005, Iraq’s first democratic institution was in place, followed by a transitional government that would be replaced by a “permanent” government after the second Assembly is elected in the up-coming election on 15th December.

Democratic steps

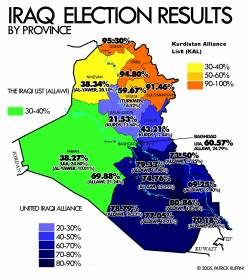

Iraq’s first elected Assembly (30th January 2005) provided clear indications of how the country’s political development would emerge. Although more than 200 political entities registered for the elections, the Shi‘a coalition, as expected, gained a clear majority in the new Assembly, followed by Kurdistan coalition. The Sunnis, who boycotted the elections, were represented by minority groups around individual politicians who returned from exile and who co-operated with other political groups and US forces to remove Saddam Hussein’s regime. At the same time, the election results also corresponded to the constituent peoples of Iraq, Shi‘a Arabs, Sunni Arabs and the Kurds, each dominating in specific part of the country and voting accordingly.

Votes, percentage and seat allocations in Iraq Transitional Assembly, 30th January 2005 elections

| Party / Coalition | Total | Percentage | Seats |

|---|

| United Iraqi Alliance | 4075295 | 48.19% | 140 |

| Kurdistan Alliance List | 2175551 | 25.73% | 75 |

| Iraqi List | 1168943 | 13.82% | 40 |

| The Iraqis | 150,680 | 1.78% | 5 |

| Iraqi Turkmen Front | 93,480 | 1.11% | 3 |

| National Independent Cadres and Elites | 69,938 | 0.83% | 3 |

| People's Union | 69,920 | 0.83% | 2 |

| Islamic Group of Kurdistan | 60,592 | 0.72% | 2 |

| Islamic Action Organization In Iraq – Central Command | 43,205 | 0.51% | 2 |

| National Democratic Alliance | 36,795 | 0.44% | 1 |

| National Rafidain List | 36,255 | 0.43% | 1 |

| Reconciliation and Liberation Bloc | 30,796 | 0.36% | 1 |

Total votes: 8456266

Total seats: 275

Source: Independent Electoral Commission of Iraq, 2005.02.17, “Seat Allocation,”

http://www.ieciraq.org/English/Frameset_english.htm

In the regional elections in Kurdistan, the secular political parties dominated the Kurdistan National Assembly.

Vote, percentage and seat at Kurdistan National Assembly, 30th January 2005 elections

| Coalition/Party | Votes | Percentage | Seats |

|---|

| Kurdistan National Democratic List | 1570663 | 93.7 | 104 |

| Islamic Group of Kurdistan - Iraq | 80237 5.1 | 5 |

| Kurdistan Toilers Party 20585 | 1.2 | 1 |

Total votes: 1671485

Total seats: 110

Source: Independent Electoral Commission of Iraq, 2005.02.17, “Seat Allocation,” http://www.ieciraq.org/English/Frameset_english.htm

The crucial process that produced the constitutional draft was concluded by a referendum (with 79% yes and 21% no votes) in which the Sunni Arabs participated. The fact that the referendum was held and Iraq’s diverse and disunited peoples participated was an achievement in itself because it boosted the political process, partly because the main political groups in Iraq managed to produce a text and partly because the Sunni Arabs’ participation gave further legitimacy to the process despite the fact that they rejected the draft constitution. The acceptance of the constitution also prepared the ground for the 15th December elections to be held and a new government to be elected by the Assembly.

| Iraq referedum by province 15th October 2005 | Yes votes | No votes | Turnout |

|---|

| Erbil | 99.36% | 0.64% | 90% |

| Salahaddin | 18.25% | 81.75% | 88% |

| Duhok | 99.13% | 0.87% | 85% |

| Kirkuk | 62.91% | 37.09% | 79% |

| Sulaimani | 98.96% | 0.04% | 75% |

| Babil | 94.56% | 5.42% | 72% |

| Diyala | 51.27% | 48.73% | 66% |

| Basra | 96.02% | 3.98% | 63% |

| Karbala | 96.58% | 3.42% | 58% |

| Muthana | 98.65% | 1.35% | 58% |

| Ninewa | 44.09% | 55.01% | 58% |

| Misan | 97.79% | 2.21% | 57% |

| Baghdad | 77.70% | 22.30% | 56% |

| Najaf | 95.82% | 4.18% | 56% |

| Qaddissiya | 96.74% | 3.26% | 56% |

| Dhiqar | 97.15% | 2.85% | 54% |

| Wasit | 95.70% | 4.30% | 54% |

| Anbar | 3.40% | 96.96% | 32% |

A federalising Iraq

In addition to the elections for transitional state-wide Assembly and Kurdistan National Assembly, voters in Iraq also elected provincial representatives in the January 2005 elections. In the December 2005 elections, only a new state-wide Assembly will be elected on the basis of a newly endorsed constitution.

Iraq’s constitution might turn out to be crucial turning point for the country on two levels. Firstly, it provides the basic elements for a federal Iraq in terms of institutional design, power-sharing, distribution of natural resources and recognition of Kurdistan as a federal unit. As to the question of other units, for example Shi‘a and Sunni regions, the decision is delegated to the new Assembly to agree on the mechanisms with which future units can be established. Secondly, Iraq’s diversity and changing balance of power is not only recognised but will be reflected in the new emerging political order and system. The Shi‘a Arabs will do everything they possibly can to consolidate their new political dominance, while the Kurds will struggle to keep what they have achieved since 1991 but also participate in re-construction of Iraq in order to ensure that they will be proportionally represented in Iraq. The Sunni Arabs, on the other hand, will struggle with the fact that they have lost their political dominance. In due time, they have to accommodate to the new reality of the political order and come to terms with the fact that they will be minority in Iraq despite all rhetoric of Arabism or Islamism or the combination of the two. Contrary to what Paul Bremer, the US administrator of Iraq during the CPA period, envisioned for Iraq in which he said that “the path to a new Iraq (is) ... where the majority is not Sunni, Shi‘a, Arab, Kurd or Turkomen, but Iraqi”, the political process in the country will be about power relations between these groups rather than any “Iraqiness”. In fact state rebuilding and re-creation in re-emerging Iraq will be based on a distinct system of power-sharing (technically called consociationalism) between the country’s constituent units rather than anything else.

Power-sharing

Since the removal of Saddam Hussein and his regime from power and the collapse of the state and its institutions in the Arab Iraq, the political process has been about establishing a power-sharing arrangement that first and foremost will include previously excluded groups in the new and emerging political order and eventually the former dominant minority (the Sunni Arabs). Like other emerging democracies, establishing democracy in Iraq would mean both division of power (between the executive, the legislative and the judicial powers) and competition of power (elections for parliament). But due to the past genocidal policies of the Ba‘thist regime against the Kurds and the Shi‘a Arabs, power-sharing in the emerging political order is viewed by leaders of both communities as the most urgent arrangement.

The basic elements of this arrangement have been to provide the Shi‘as and the Kurds to jointly re-create Iraq and if possible govern the country. Since the creation of the Governing Council Americans and Shi‘a and Kurdish leaders have both encouraged and made it possible for Sunni Arabs to be part of the process. Another element of the power-sharing arrangement has been the principle of proportionality in the government and other state institutions, in the Governing Council and the Transitional Assembly and in terms of allocation of resources. A third element is the idea that partnership in a new and re-create Iraq must be based on the principle of equality which would allow for meaningful self-rule and institutional recognition. Politicians from Kurdistan have worked eagerly to implement this idea before the removal of Saddam Hussein’s regime and more so since the creation of the Governing Council. A fourth element of the power-sharing has been veto-right for constituent peoples and units of re-constructed Iraq.

The main questions since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime has been whether a power-sharing arrangement is desirable by all peoples and units of Iraq; whether such an arrangement is realistic in the current situation in Iraq; and whether power-sharing arrangement is suitable in re-constructed Iraq. The answer to the first question is that both political leaders of the Shi‘a Arabs and the Kurds would have seen it as the only viable solution since both communities were excluded from previous arrangements for decades. They also see such an arrangement as realistic because a clear majority of the country’s population would be included. In the longer run, they hope, the Sunni Arabs will also realise that such an arrangement will protect them far better than any other solution. Both Shi‘a and Kurdish leaders see a power-sharing arrangement as a suitable political solution because it will prevent recurrence to past policies of genocide and massive repression by the Sunni Arabs.

In fact power-sharing arrangements in deeply divided territories and societies have the potential to prevent the government from being ethnic cleansers. It will also support political settlement for failed policies that focused on violence and repression. Instead of focusing on assimilation or integration, power-sharing arrangements will allow for constituent peoples and units to live together side by side within an agreed political system. This element is possibly strengthened by the fact that leaders of all communities can live with the idea that there is more than one people within the country and that every people or unit has reasonable claims to power-sharing, representation and justice. By not insisting on a shared identity or vision for the country, power-sharers can easily focus on shared interests and shared fears of recurrent violence. In the case of Iraq, the only group that will oppose such a framework is the ousted Sunni elites who have lost power. By encouraging to join the process the Sunni Arabs, Shi‘a and Kurdish leaders seem to hope that for former dominant minority will eventually accept the new arrangement because it will be equally beneficial for the Sunni Arabs, as well as for other groups in Iraq.

If this arrangement to be taken seriously, the actors expect the separate societies or peoples of Iraq to be recognised and respected; instead of talking about one society or one people, plurality of peoples and societies would not been seen as political heresy, as it is the case in the Middle East. Instead of conflict and confrontation, separate groups in Iraq co-operate to find viable political solutions to political problems. In this context it is not impossible to imagine peaceful co-existence of two or more peoples in a re-constructed Iraq. After all, Iraq would not be the only country in which past violence orientations can be replaced by a new political order, leaving behind the idea of institutional superiority of one people over the others. Self-rule and shared-rule would strengthen political co-operation between the elites of the constituent peoples because power-sharing allows dealing with different levels of competencies in order to respect equality between partners and make peaceful co-existence a meaningful enterprise. Since power-sharing arrangement is not easy to pre-plan, its emerging characters makes it both complicated and subject to the political willingness to constantly re-negotiate the arrangement when basic conditions of the power-balance between constituent peoples and units have changed.

A federal constitution

One important aspect of the approved constitution of Iraq is that it contains both traditional democratic division of powers (between executive, legislative and judiciary) and shared power between constituent units (federal executive power, shared competencies between federal and regional authorities). One remarkable aspect of power-sharing is that the constitution gives priority to the regional laws in case of conflict between federal and regional authorities. Article 111 stipulates that “All powers not stipulated in the exclusive authorities of the federal government shall be the powers of the regions and governorates that are not organized in a region. The priority goes to the regional law in case of conflict regarding other powers shared between the federal government and regional governments.” If used constructively, this article can prevent centralisation of power in Iraq, especially if Kurds and Sunni Arabs want to block Shi‘a Arab domination.

While it is not easy to see any peaceful co-existence throughout Iraq at the moment of writing, people in Kurdistan have already started to enjoy a degree of freedom they have missed for generations. As a refugee returning to the problematic city of Kirkuk expressed it, “it’s a great feeling to be free. It’s a great feeling to live in peace and not feel any threats from a tyrant like Saddam. If this house is taken away from me, I live in a tent. If the tent is taken away and I am forced to live under a tree, I’ll still be free.”

* Senior Lecturer, PhD

Centre for Contemporary Middle East Studies, University of Southern Denmark

|