Sunday, December 9, 2007 | Reviewed by Quil Lawrence

How a rebel group has tried to capture a people's aspirations.

The guerrillas of the Kurdistan Workers Party, known by the initials PKK, are stuck in the mountains, literally and figuratively. The Kurdish rebels know every mile of the rough peaks and deep gorges along the borders of Iraq, Turkey and Iran. They have cliff-side bunkers, black-market supply routes and plenty of ammunition. What they lack is a path forward.

This fall, the PKK made a series of bloody raids into Turkey from its hideouts in northern Iraq, killing dozens of Turkish soldiers and practically daring the Turkish military to mount a large-scale, cross-border retaliation. This situation is precarious not only for the rebels, but also for U.S. forces. The Turks, who have massed tens of thousands of troops close to the Iraqi border, have been pressing the United States for years to crack down on the Kurdish independence movement. The U.S. military, however, has little to gain from opening a new front in Iraq. Twice in the past six months, the tensions have threatened to blow up into a full-scale war involving Turkey, Iran, Iraq and the United States -- the only question being exactly who would be allied with whom.

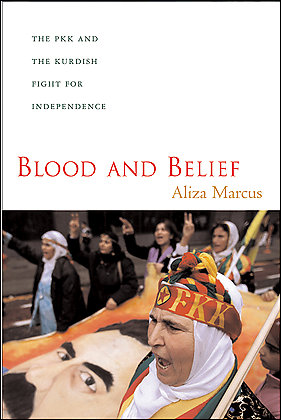

How this came to pass is the subject of Aliza Marcus's timely book on the PKK and its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Ocalan. A former correspondent for the Boston Globe and Christian Science Monitor, she draws on eight years of experience covering the Kurds and a vast reservoir of interviews with PKK fighters.

Blood and Belief begins with the formation of the PKK in 1978 by disaffected Kurdish students in Turkey. Ocalan's own beginnings are somewhat comical; his marriage to the daughter of a middle-class politician, he once said, was proof of his ability to withstand any hardship the rebel life had to offer. But his guerrilla career was anything but funny. In the 15 years after the PKK launched a separatist war against the Turkish state in 1984, the fighting claimed some 35,000 lives, mostly poor Kurds in southeastern Turkey. In 1999, the United States helped Turkey arrest Ocalan, who had fled to Italy and Russia and was finally captured in Kenya. Since then, the few thousand PKK fighters left in the mountains have stumbled between cease-fires and ultimatums, unable either to cut ties with their jailed leader or to figure out exactly what to do next.

On a recent journey to a PKK outpost inside northern Iraq, I found the rebels living in psychological as well as physical denial. "Why does everyone call us terrorists?" one Kalashnikov-toting Kurd asked. "The Turkish government has given the Kurds no rights, no schools, no language. We have a right to live in freedom."

The Kurds surely have a cause, but the PKK's disregard for civilian lives has put them on terrorist blacklists both in the United States and in the European Union. The guerrillas hint that they would stop fighting if offered a blanket amnesty. But they show no savvy about how to improve their image, especially their cult-like devotion to Ocalan.

Marcus's book helps explain this, too, by chronicling the horrifying business of the PKK's consolidation of power. Her account of Ocalan's quest to become the sole voice of Turkish Kurds is the first of its kind in English, describing the PKK's savagery toward groups that should have been fellow travelers in the fight for Kurdish rights. Ocalan shared the penchant of dictators around the world for killing any perceived rival, at times discrediting or executing even his most able lieutenants. It's an achievement of Blood and Belief that despite the bloodletting, Marcus still generates empathy -- not for the murderous Ocalan, but for the desperate Kurds who joined the PKK revolution feeling they had nowhere else to turn.

The book is not always an easy read. It suffers from the lack of a decent map, and sometimes the narrative becomes disjointed among all the changing names and factions of the PKK. On the other hand, Marcus is compelling as she describes the PKK fighters who continued with the cause, believing it was greater than Ocalan's obvious flaws. She conveys the trapped feelings of Kurdish boys and girls who train under a mural of Ocalan's face painted on a cliff. And she brings home the most important point: The PKK hasn't been rousted from its mountains in two decades of fighting, and there's no reason to think another Turkish incursion will bring the rebels down. *

Quil Lawrence is Middle East correspondent for the BBC/PRI radio program "The World" and author of the forthcoming book "Invisible Nation: How the Kurds' Quest for Statehood is Shaping Iraq and the Middle East."